The Ecologist – Never ‘Just’ a Magazine

The Ecologist was never ‘just’ a magazine. There were some years when it didn’t look or read like a magazine at all.

The Ecologist was a state of mind, a way of thinking and being and feeling. It was a little flame nurtured and kept alive in the hearts of those who believed that the world could change for the better.

To me its ‘end’ as an independent entity is in many ways a sad metaphor for the very things it fought against. Teddy Goldsmith founded the publication with a deep love of all things wild and natural and a deep disdain for those arrogant men who would claim the right to dominate, to change, to tame, to pollute, to genetically modify the true nature of anything to suit some artificial notion of progress. That overriding principle – a kind of environmental commitment to “first do no harm” informed our work almost to the end.

Working there was never easy but I don’t think any of us went there looking for ‘easy’. We went there to pool our talents, our insights and our expertise and produce something extraordinary. The thing we produced was dubbed by the New York Review of Magazines “a magazine that changes people’s lives”. And it did. The letters and emails I received every day were testament to that fact.

The nuances of the full Ecologist experience are hard to convey to anyone on the outside. I could talk about all the crap that went on. Like any office anywhere in the world there was plenty of that. But that was not my take-home experience of being Health Editor then Editor of the world’s oldest and most respected environmental magazine.

In the office, as well as in print, the Ecologist had a culture of challenge that many people found difficult to cope with. It was a tough, and until I arrived, fairly macho culture. In many ways it operated more like a think tank. Nothing was sacred. Every thought could be questioned, every assumption tested, every opinion disputed, every ‘great idea for a story’ shot down if you weren’t strong enough to fight for what you believed in.

Having enough self-belief to see a feature through this sometimes irritating process, was part of what made the editorial so compelling and courageous and ahead of the curve. If you cared enough to fight for your story, that passion was always going to translate into something that would inspire (or infuriate) others. Either way it was a win.

The offices in Chelsea where I started provided a funky, chaotic backdrop to a group that was always laughing, plotting, shouting, crying, swearing… and cooking. Strong black coffee and not very eco, or healthy, golden Gummy Bears were the preferred fuel of press day. Occasionally the editorial meetings took place at Aspinalls – could there be a more unlikely venue for subversion?

I got yelled at so many times in the first few months by the then managing editor that one day, devastated by more than two hours of shock and awe, locked in the kind of ‘conversation’ where the first person to breathe is declared the listener – followed by three hours of sobbing – I typed out my resignation. I was always glad I never sent it.

The Ecologist was a pain in the ass. It was inspired. It was prescient. It was opinionated. It could be shocking. It was on occasion poorly proof read. It was run on a shoestring and it always, always punched above its weight. What we had to say wasn’t always popular, but we were rarely wrong. And, uniquely for a monthly, we were generally first.

It was brave publication – probably more brave than anyone on the outside could ever imagine.

When Tate & Lyle took offence at my questioning the safety of its sweetener, Sucralose, it threatened to sue. It was the first major article I’d written for the magazine – this in the days when a feature article could stretch to 10,000 words.

Zac Goldsmith said he wanted to talk to me about it and I was expecting to be told off or worse, fired. Instead he asked if I was sure of my facts. I said emphatically yes. Without a moment’s hesitation he said, “Then we’ll fight it. Close the magazine if we have to.” For him that’s what the Ecologist was there for. To get to the truth, to expose cynicism, stupidity and wrong-doing, get under people’s skin, and wake them up from their complacency and make them think.

In this instance my strategy, such as it was, was simple: for every 10 pages of complaint they produced, I produced 20 pages of evidence and counter argument for our solicitor to send back to their solicitors. After long months of wrangling they dropped the case. That scenario repeated itself a few times, for instance when pharma giant Roche objected to my criticisms of its cancer drug Herceptin.

It’s hard to convey just how rare and deeply empowering it is for a journalist to have such unwavering support through both good times and bad.

In fact, the Ecologist was never successfully sued. Over the years lots of big bads, including Monsanto and De Beers tried, but none succeeded because outspoken editorial was always backed up by solid research and a refusal to bow down.

Try to run some of the groundbreaking pieces we ran in any other newspaper or magazine and the story would be killed by the legal department before it ever saw the light of day.

Our solicitor, on the other hand, a libel specialist, cheerfully encouraged us to publish and be damned, knowing what most of us know instinctively – that all bullies are cowards.

Were we protected from the ‘realities’ of magazine publishing? Sometimes. For most of its life the Ecologist never had to kowtow to advertisers or big business, but relied instead on subscription income and the support of the Goldsmith family. Were we privileged? Certainly. But privileged in the sense that our owners understood the kind of beast it was, and the kind of beasts we were fighting. They understood the importance of independence and the price – fiscally, but also in terms of popular opinion – of that independence.

We also had a higher purpose. Indeed, what gave us courage was the vision of a world where magazines like the Ecologist would no longer be necessary. While other media outlets busied themselves building empires and networks, trying to get one hairdo to outdo the other side’s hairdo in the ratings, currying political favour, tapping phones, hacking emails and building monuments to the greatness of their boards of directors and executives, we were angling for our own mortality – and maybe a little smallholding somewhere where we could put all this stuff we were writing about into practice. Show me any other media outlet where that is the motivating factor.

It is a source of real sadness to me that the Ecologist hasn’t lasted long enough to see that day.

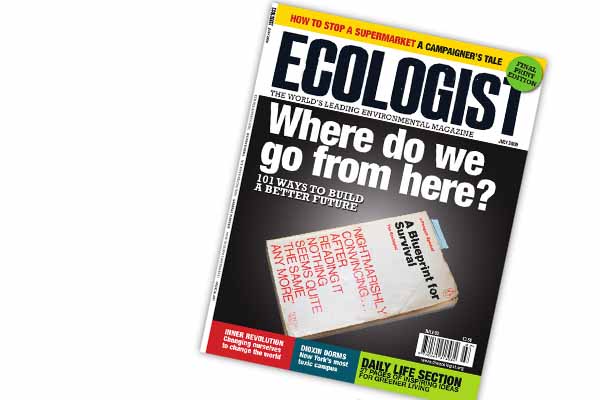

I left in 2009 when the magazine abandoned print and morphed into a website. I received piles of heart-breaking letters and emails from readers and from my extraordinary contributors who felt the loss personally.

Beyond my contractual obligations I barely contributed to the site after I left, though I was often asked. Apparently Google analytics ‘proved’ that my back catalogue was popular with visitors. It’s ironic to me that having been convinced to contribute one more longform piece – to a birth special, conceived by the last remaining member of my original staff – that work gave the website its biggest day since its launch.

People are hungry for good journalism, for context and insight and for passion. They are tired of features generated largely on the basis of ‘that worked really well for Google analytics, can you write it again… and again and again?’

To my mind the demise of the Ecologist can be laid at the feet of a series of dimwitted Google-eyed executives who seemed to equate visitors with readers and didn’t appreciate or care that the Ecologist was a force of nature. People who couldn’t comprehend its achievements save that they could be reduced to a slogan or sales pitch. People whose insight only stretched as far as trying to turn something so much bigger than a magazine into just another populist title.

If nobody much notices its absence, that lack of vision will be why.

To watch an iconic, once powerful force become a shopfront for green lipstick and eco spa days, while its longform investigations, its raison d’être, were hidden largely behind a pay wall that most web trawlers probably didn’t even know or care existed, was excruciating.

It’s no secret that I argued vociferously for it to remain in print and it’s, again, ironic that the rather low key announcement of the merger with Resurgence talks about the Ecologist ‘returning to its roots in print’. Whether it returns with its tail between its legs or its head held high remains to be seen. The fact that it took the newspapers – many of which would not have environment pages had it not been for the Ecologist – 5 days to respond to the press announcement doesn’t bode well.

To those of us who loved it, and I mean really loved it, and who felt the pulse of the beast and were happy to run with it, the loss of the Ecologist as an independent entity provokes the same deep grief as the loss of a family member.

I can say hands down it was the best job I ever had. It was the place that brought my soul brothers, my soul sisters and my soulmate into my life. It was home in a sense so deep I can hardly describe it without aching. I am profoundly grateful to have had the opportunity to be a part of such an extraordinary experience.

My dear Ecologist, unashamedly and with all my heart, this is my love letter to you.